In 1992, after having directed two striking films (Ju Dou and Raise the Red Lantern) that set him at odds with the Chinese

Government, Zhang Yimou released TheStory of Qiu Ju, an unexpectedly repentant specimen. The film may have compromised Yimou’s

relationship with his viewers, but it also seems to have subversively addressed

the compromises that Yimou had to make in order to remain a filmmaker.

The nature of the relationship between an author and the

reader or consumer of his work is explored by Jean Paul Sartre in his essay, What is Literature?. In it, Sartre contends that “literary objects

exist only in the concrete act of reading,” and that any meaning tied to any

text is actually contained within the individual who is creating or consuming

the text, and that the texts on their own are merely black squiggles on a page. Through shared language, the author entreats

the reader to “create meaning” out of the text, thus the author uses their

freedom to create a text to entreat to the reader’s freedom to engage with the

text and create meaning.

Sartre explains, “The writer appeals to the reader’s freedom

to collaborate in the production of his work…. The work of art is a value

because it is an appeal.” The reader,

freely choosing to open the text and engage with it is “asserting that the

object has its source in human freedom.”

Thus the effective relationship or dialectic between an author and a

reader is one of mutual respect and freedom.

Sartre felt that authors who failed to respect the freedom of the reader

(citing and criticizing Pierre Drieu la Rochelle) decimated the potential for

reader engagement or reader meaning-making.

So how was Zhang Yimou, who was reportedly under pressure to

paint authority and government in a more positive light if he wanted to remain

in his profession, to avoid becoming an irrelevant sycophant like Drieu la

Rochelle? If he felt, like Sartre, that

the meaning in his films was actually constructed by the audience, then perhaps

The Story of Qiu Ju is his way of

entreating the audience to understand the necessary pitfalls of working within

an imperfect system, and even to forgive them in him and his work. It was, perhaps an extension of the act of

faith that Sarte described: “The bad novel aims to please by flattering,

whereas the good one is exigence and an act of faith.”

The film centers around the determined Qiu Ju, played by

Yimou’s perennially favorite actress Gong Li.

Loosely based on the novella, The

Wan Family Lawsuit, by Chen Yuan Bin, the film follows Qiu Ju, a determined

country wife, as she doggedly follows every channel legally available to her in

order to satisfy her need for justice, which is (to her) an apology from her

village chief. Only, Qiu Ju’s version of

justice is impossible to enforce and is not even comprehended by most of the

well-meaning government bureaucrats depicted in the film. Repeatedly the courts rule that the chief

must provide pecuniary retribution, which he offers with demeaning vitriol, and

which Qiu Ju feels morally compelled to decline. Ultimately she has pursued vindication to

such a length that the chief is imprisoned for his crime even after Qiu Ju has

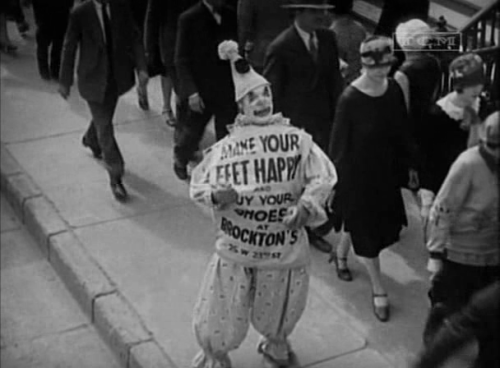

forgiven him and is earnestly seeking his good favor again. The film regularly depicts the incongruence of

Qiu Ju’s enceinte rube amidst the bustle of the modern city. Her character is clearly as much comedic as

tragic, especially for a Chinese audience.

She is in many ways more of a child than an adult.

In view of the Confucian thinking that would underpin a

Chinese encounter with the film, the fact that neither Qiu Ju nor the Chief

seem interested in restoring harmony renders both of their approaches to the

conflict as silly. When Qiu Ju insists

to her husband that she doesn’t care what others in the village think of her,

rather than the admiration for integrity that an American Audience might incur,

a Chinese audience would have been more likely to see her behavior as

needlessly reckless, contributing to her tragicomic end as the siren wails,

symbolically asking Qiu Ju, “What have you done?”

What meaning might Yimou have been hoping that his audience

might make of this work? Especially of

his ambiguous ending as the film freezes, unresolved, on Qiu Ju’s face as she

pursues the vehicle with the arrested chief?

It seems that perhaps Yimou was asking questions with this film about

impossible situations and hoping that his audience would recognize that they

were unanswerable, as Yimou found himself in an impossible situation, and felt

that his work would be compromised or destroyed no matter how he chose to

proceed. Yimou continued to make films

in China within the parameters of government pressure, and complied well enough

to be given government commissions (including the 2008 Olympic opening ceremony).

Though in interviews has consistently tried to distance himself from government

influence.

The film itself seems to be a disclosure of the necessity

for recognition of limits and for compromise – for working within the

constraints of an imperfect system in order to work at all. The film very mindfully portrayed every

individual except Qiu Ju, the chief, and the city taxi driver as gracious and

amenable. The only conflicts that were

allowed to surface in the film were between Qiu Ju and the chief (technically

this involved Qiu Ju’s husband, but he was prepared to let it rest long before

Qiu Ju was), and between Qiu Ju, her sister-in-law Meizi, and the city taxi

driver. The conflict with the taxi

driver plays out like the other, larger conflict in miniature. For his petty misconduct, Meizi chases him

into the unknown, subjecting her family (Qiu Ju) to angst, and her efforts

prove fruitless – more harm than good is done.

By representing Qiu Ju’s futile, sometimes bull-headed

attempts, Yimou is clearly crafting some meaning. Whether Qiu Ju’s zeal is intended to be

symbolic of Yimou’s own in his past is essentially an opportunity for guided or

“directed creation.” The viewer can

finish what Yimou has begun – but whether they draw a line connecting Qiu Ju

with Yimou’s earlier films depends on what information the viewer brings with

them to their viewing.

Existing government systems did not allow Qiu Ju to pursue

or achieve her definition of justice, and when she worked within those systems,

the result was a disappointment, but she was still willing to persist. Is Yimou asking whether it will prove a

similar disappointment if he seeks after artistic freedom in a similarly non-ideal

system? He interestingly asks the

question without answering it, allowing the audience their own creation of

answer and meaning.

Sartre claimed that a “literary object has no other

substance than the reader’s subjectivity.”

Citing Raskolnikov’s hatred of the police magistrate who questions him

in Tolstoy’s Crime and Punishment he

claims, “Raskolnikov’s [hatred of the magistrate] is my hatred which has been

solicited and wheedled out of my by signs, and the police magistrate himself

would not exist without the hatred I have for him via Raskolnikov. That is what animates him, it is his very

flesh.” We see this authorized existence

and fleshing out of the chief morph before our eyes as Qiu Ju experiences a vulnerable

crisis and is rescued by the Chief’s efforts.

Prior to that point, the chief is only ever represented (by presence in

a scene or by description of other characters) as being stubborn and

prideful. Suddenly his character becomes

infinitely more complex by doing something out of character. Viewers are invited to forgive the chief

along with Qiu Ju. At this point harmony

is restored, except for the avalanche Qiu Ju’s previous, rather naïve legal

actions set in motion. The chief is

arrested and harmony is obliterated, and Qiu Ju’s “what have I done?” face

becomes the film’s signature moment.

It is possible that this film is an entreaty (to the freedom

of the viewer) to consider the complexity and imperfections of the systems

under which they and Yimou alike strive to function and create. The film carefully points no antagonistic

fingers. Everyone is likeable and

agreeable (to Qiu Ju) by the end of the film, and what remain are mistakes, not

sins. It may be that Yimou was hoping to

invite his viewers to apply a similar compassionate judgment to both his past

and future work as he endeavored to change gears and comply with government

pressure.