Doug Block: Autobiographical Mode

Thursday, May 29, 2014

Documentary: Sherman's March (1985)

Documentary: Mode Activity 2

There was a substantial learning curve in store for me as I headed into this project with a concrete idea for an expository documentary piece. First of all I got to encounter the roadblock of reality not matching up with my preconceived story. I simply didn't get the reactions or the shots that I had in mind, because the illustrative moments I was counting on didn't happen. But secondly I got the experience, appropriate for an expository project, of determining what story did exist in the footage I had captured, and of finding a way to be as transparent as I could with my audience about the whole experience. Despite an appearance of "honesty" or disclosure in this piece, I still had power over what was included and excluded, so it was enlightening to see how something that can appear so raw can still be so thoroughly constructed. (Though frankly- half-constructed here; my audio and transitions are awfully rough.)

My original concept here was to be clever and explore the process of watching a documentary. I was planning on an animated subject, giving me somewhat explosive, highly charged responses that would be easy to inject the meanings of my choice into. Instead I got the most solemn and still face I've ever seen on my subject (Mary Ila) for the entire hour duration of the film she watched. I had to figure out what to do with it, and since I was already intending to create something reflexive, I got to be reflexive about the process of filming and interviewing her (and even the process of trying to interview myself, which - sheesh.) It seems like this "what went wrong" formula may be likely to surface in expository documentaries, as it becomes the most available vehicle for constructing a story when your original plan falls through.

So ultimately I suppose I've created a cautionary tale here about interviewing the hearing impaired. There are certainly complications revealed here about the process that I didn't think to anticipate before I began the interview. Ultimately that experience of realizing what it is you don't know while you're on your feet, trying to create something, is really kind of stunningly informative; a most thorough way to learn.

Monday, May 26, 2014

Documentary Online Response #6: Reflexive Mode

According to Nichols[1], “Reflexive documentaries ask us to see documentary for what it is: a construct or representation.” A reflexive documentary is therefore a use of a medium to explore the phenomenological mechanics of its own medium, which certainly seems in keeping with post-modern reflexivity and intertextuality in other mediums. Perhaps this is more resonant in documentary because of the reputation for objectivity and omniscience that more traditional modes, such as expository and observational, may have established for the entire medium/genre of documentary film. We see a similar self-reflexive tendency in fiction films such as Day for Night (1973) that explore the process of creating a fiction film, or in a Mel Brooks parody like Blazing Saddles (1974) or Young Frankenstein (1974), making fun of fiction genre conventions and addressing the audience directly, but it seems that a documentary being reflexive about its own creation feels a little closer to the source, a little more willing to be vulnerable about its own limitations, and far less likely to use self-reflexivity toward a comedic end, as comedy tends to imply a control that seems incompatible with self-reflexivity about social actualities.

This integral vulnerability came across strongly in This is Not a Film (2011), in which

Jafar Panahi was on several occasions open to the ambiguity of the project, and

how it was not going to turn out to be the original project he had devised (a

reading of his banned script.) but was instead evolving into something more

complicated and nuanced.

It seems like, while elements of self-reflexivity may be

becoming more common across all documentary modes, a primarily reflexive mode

would be difficult to pull off, as it would require either an immense willingness

to show vulnerability and fallibility from the filmmaker, or else an enormous

ego; or perhaps, in the case of a filmmaker like Nick Broomfield, a bit of

both. In a film like Driving Me Crazy

(1988), Broomfield chose to be willing to portray the frustrations his subjects

had with his film crew, but he was also willing to show some of his financial

backers in an unflattering way. He

certainly allowed himself, his small crew, and his subjects to all be portrayed

as parts of a complicated relationship, which in turn allowed for an engaging

portrayal of the ups and downs of documentary production.

Nichols went on to say that reflexive documentaries “examine

the nature of (such) belief rather than attest to the validity of what is

believed.” This felt especially true

about Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin’s Chronicle of a Summer (1961), where, in

the final sequences the subjects view and discuss the film made thus far. Watching the ways that they arrive at

different conclusions about each other as social actors, and about what worked

best in the film, invited introspection into one’s own perceptions and

relations with the same footage, as well as requiring a concession that

opinions other than one’s own could be deduced from the exact same film

sequences; which ultimately invites a certain vulnerability from the audience

as well.

Thursday, May 22, 2014

Documentary: This is Not a Film (2011)

Reflexive Mode: The difficulties of making something.

Wednesday, May 21, 2014

Documentary: Chronicle of a Summer (1961)

For Reflexive Mode. Most reflexive in the last 10 minutes, and the entire film makes more sense in context of the Algerian War.

Tuesday, May 20, 2014

Documentary Online Response #5: Participatory Mode

Our entire class found Nobody’s Business to be a delightful

change of pace when we viewed it for participatory mode, largely because the

filmmaker, Alan Berliner’s, relationship with his father becomes the center,

catalyst, and purpose of the film. The complexity of this relationship shows

through in the first sequence of the film and develops ever more nuance and

weight as the film progresses.

The way in which Alan Berliner allows his father to

constantly condemn and redeem himself in the course of the film’s interview

dialogue shows a great amount of charity and investment in the relationship. It would have been incredibly easy to edit

the same conversations to make his dad seem irredeemable, but that never

happens. Oscar Berliner is always

allowed to finish his thoughts, so that his outlandish initial sound bite

statements are softened by explanation and context, and sometimes even by the

arguments they provoke. Certainly the

sequences explaining and illustrating the intense loneliness of his father’s

lifestyle evoked a sense of explanation and forgiveness for some of the more unfeeling

words his father threw at him.

Certainly Berliner came across as more of an essayist than a

historian. He also embodied Nichol’s

statement that, “It is the filmmaker’s participatory engagement with unfolding

events that holds our attention.”[1] As Alan Berliner’s participation, catalysis,

and provocation were the glue and the impetus that kept the entire film

cohesive and kept me as a viewer engaged.

Berliner’s own sense of family, identity, and relationships became the

normalized perspective against which to judge his father’s alternate value

set. The film felt inevitably structured

to evoke sympathy with Alan Berliner’s perspective and values, but also to

provoke a complicated, redeemed affection for Oscar Berliner who so frequently

antagonizes him.

It seems that without the voice of Alan Berliner, and the

sense of him navigating his relationship with his father, it would have been

difficult or impossible to portray his father with the same dignity and

likeability. The obvious affection that

Berliner has for his father is what allows the audience to repeatedly forgive

Oscar for his belligerence and folly.

Documentary: Nobody's Business (1996)

Totally engrossed in participatory mode. And fascinatingly engaging.

Monday, May 19, 2014

Documentary: Harlan County USA (1976)

Participatory Mode - once it gets interesting.

Sunday, May 18, 2014

Documentary: Mode Activity 1

(Expository/Observational/Poetic Mode)

Documentarist's Statement

Due in large part to time constraints, I did not write, record, and add a voiceover narrative to this piece. I could have easily transformed this into a straightforward use of either expository mode or an essayistic version of the poetic mode with a voiceover, depending on what approach I might have taken. I could have described my son's activities with the sterile voice of an anthropologist, or with the sentimentality of a mother-poet. (I think it would be interesting to have him describe his own actions, but that would push the project into other modes). The use of a music soundtrack could have also easily lent poetic voice to the piece, and probably helped in an effort to cover up off-camera noises.

As it is currently edited, I feel that this project aligns most with the observational mode, although because I'm the one who filmed it and edited it together, I'm keenly aware of its constructed nature, and of all the omissions, as well of how differently it could have looked if I had made different choices, especially while filming. I'm wishing I had gotten some different perspectives - his hands coloring at their level, from a perpendicular angle, and possibly an overhead shot. I also really wished my shots were longer when I was editing them together. All but one of them were at least 10 seconds long, but I found I needed several longer (probably wide) shots to ground the whole piece, as well as explanatory shots for all the off-camera-noises (of which there were many.)

Because I was filming my own son, it would have been pretty impossible to have fully embraced an expository mode. I have too much of a relationship with my subject to create a viable impression of objectivity. But this project fits one of the descriptions of the spirit of observational filmmaking. It contains "no voice-over commentary, no supplementary music or sound effects, no inter-titles, no historical reenactments, no behavior repeated for the camera, and not even any interviews."(Nichols.) Actually, that's not true. We did have to repeat his entrance shot for the camera, he was too nervous about its presence the first time, and clean entrances and exits were part of the assignment.

But interestingly, Nichols claimed that "Observational films exhibit particular strength in giving a sense of the duration of actual events," and this film, in total, is about the length it would normally take my son to color this picture. When I was filming, I found that everything took longer because my son behaved differently with the camera in the space, and was far less comfortable in his processes than he normally is. So the finished product here is a reasonably close representation of what would have happened without the camera present, while what happened with the camera present, while I was filming this, was a much more awkward and halted process. I'm still deciding how I feel about that in the context of observational mode editing.

_________________________

Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary. 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2010. Print.

Documentarist's Statement

Due in large part to time constraints, I did not write, record, and add a voiceover narrative to this piece. I could have easily transformed this into a straightforward use of either expository mode or an essayistic version of the poetic mode with a voiceover, depending on what approach I might have taken. I could have described my son's activities with the sterile voice of an anthropologist, or with the sentimentality of a mother-poet. (I think it would be interesting to have him describe his own actions, but that would push the project into other modes). The use of a music soundtrack could have also easily lent poetic voice to the piece, and probably helped in an effort to cover up off-camera noises.

As it is currently edited, I feel that this project aligns most with the observational mode, although because I'm the one who filmed it and edited it together, I'm keenly aware of its constructed nature, and of all the omissions, as well of how differently it could have looked if I had made different choices, especially while filming. I'm wishing I had gotten some different perspectives - his hands coloring at their level, from a perpendicular angle, and possibly an overhead shot. I also really wished my shots were longer when I was editing them together. All but one of them were at least 10 seconds long, but I found I needed several longer (probably wide) shots to ground the whole piece, as well as explanatory shots for all the off-camera-noises (of which there were many.)

Because I was filming my own son, it would have been pretty impossible to have fully embraced an expository mode. I have too much of a relationship with my subject to create a viable impression of objectivity. But this project fits one of the descriptions of the spirit of observational filmmaking. It contains "no voice-over commentary, no supplementary music or sound effects, no inter-titles, no historical reenactments, no behavior repeated for the camera, and not even any interviews."(Nichols.) Actually, that's not true. We did have to repeat his entrance shot for the camera, he was too nervous about its presence the first time, and clean entrances and exits were part of the assignment.

But interestingly, Nichols claimed that "Observational films exhibit particular strength in giving a sense of the duration of actual events," and this film, in total, is about the length it would normally take my son to color this picture. When I was filming, I found that everything took longer because my son behaved differently with the camera in the space, and was far less comfortable in his processes than he normally is. So the finished product here is a reasonably close representation of what would have happened without the camera present, while what happened with the camera present, while I was filming this, was a much more awkward and halted process. I'm still deciding how I feel about that in the context of observational mode editing.

_________________________

Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary. 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2010. Print.

Thursday, May 15, 2014

Documentary: General Orders No. 9 (2009)

Robert Persons. Poetic Mode -

Documentary: Mothlight (1963)

Stan Brakhage. Poetic/Painter mode.

Wednesday, May 14, 2014

Documentary: Night and Fog (1955)

Alain Resnais - Poetic/Essayist Mode. Because grad school must include a quota of harrowing.

Documentary: Glas (1958)

Bert Haanstra - Poetic mode. Incredibly precise use of soundtrack to create something artful.

Documentary: Rain (1929)

Joris Ivens - Poetic Mode

Documentary: Observation Exercise

8am - this is my weekday ritual of wrestling my 7-year-old out of bed and into his clothes. This child needs something like 13 hours of sleep to function well, so morning always comes too soon. His reticence and petulance are most evident at this time of day - just check out that body language. It's also the time of day when I rediscover, over and over again in low light, how long and lithe this body has become that I once built inside of me.

9:30am - my younger two boys have been told that they cannot play video games unless they can agree on what to play in advance. That proved too difficult, so they resorted to pretending the laundry baskets are rocket ships again. (Which may have been my plan all along.) My 3-year-old is potty training, so he only wears pants when he leaves the house. His little legs have lost most of their baby fat (that light on his legs!), but he's still got it in his cheeks. And he still fits in a laundry basket.

We call her Bunny, and despite being only 18-months-old, she has developed a radar for portable electronic devices and she gets laser-beam-intent on figuring out how to navigate them, while sitting on the kitchen floor. Such a digital native. Also - this captures the conundrum of her hair really well. She won't hold still enough to do a real braid, so we go through a dozen disposable hair elastics every day, and it takes up to 20 minutes to wrestle them all into her hair. The not-quite-symetry in this shot sort of complements her intensity.

Dishes - one of the tasks I tackle multiple, multiple times every day. Because I didn't want to try to find beauty in cleaning my boys' bathroom. Poetry in the Prosaic. Emily in the reflection. Over and over and over.

I did a lot of gardening in the late morning, mostly preparing beds and soil for planting that should have happened last week. But the light outside was too harsh for a good photo. So right as I was finishing I dropped my gloves and trowel on the rug in my garage and grabbed the camera. I finally managed a photo with enough depth of field to have something in focus. I am a visual texture junkie, and so these lambskin gloves make me happy to look at.

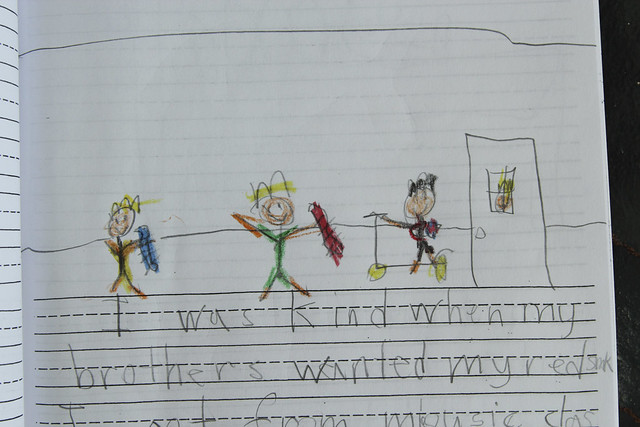

My 7-year-old came home from school with his April writing journal. This is an entry about how he was kind when he let his younger brothers play with his plush snakes while he was at school, (he would never think to share when it was inconvenient for him - the turkey) but I love it because it captures a lot of things about our mornings. My son has drawn himself with his red and blue star backpack and his scooter, and our neighbor that comes and waits in our front room every morning while my son drags his feet brushing his teeth and getting his jacket on is standing outside the front door. He even drew his 5-year-old brother wearing his favorite color, green.

Bob left this behind after class. Everybody stayed a few moments after Night and Fog ended to process and decompress, and I think this poor stem is a pretty apt metaphor for how emotionally bereft we all felt.

The carpet and rug at the top of the East Stairs of the D-Wing of the HFAC. Mostly because I love all the texture going on there. The patterns in both carpets, and the difference in frieze between the two fibers, and that nubby little strip of rubber between them.

As soon as I got home from class, this girl was ready for bed. She is a thumb-sucker of the first order. She also has a blankie that she has attached herself to. (See the fabric between her fist and her neck? It's also under her pointer finger as she manages to simultaneously suck that thumb and rub her sweet spot on the blanket) I also kind of love that shine in her hair, because thank-heaven my babysitter bathed everyone and got them into pajamas for me. And the way her hair falls in her eyes is maddening in real life, but adds a lot of interest to this photo. Also - taking this photo while holding her was a trick, but it almost captures the way she clings to me when I'm coming and going. I am her third comfort item.

My 5-year-old, and his joy-face, upside down, hair still wet from his bath. Chewing on his shirt, and his scar on his cheek from the stitches he had to get after splitting his face open in preschool a while back - all reminders of his apraxia. I don't see the scar when I look at him anymore, but I see it when I'm looking at photos. And yes - those are Boba Fett pajamas, and they are compounding his joy. He was facing the window at this moment, and the outer light is complementing his inner light really well. See those catchlights in his eyes?

While my boys were doing gymnastics in the living room, I looked out the front window and noticed that the setting sun was backlighting these pansies so they sort of glowed. I hoard moments like that in a special spot in my brain, a reserve for when life seems colorless. I had to set the camera on the ground, back it up for focus and zoom in to get a shot, but I think it captures some of the luminescence that was happening.

And while I was in the front yard, I also got a shot of my tree peonies, because they are gorgeous, but they last about 3 days. Fleeting, fleeting ruffley things, in the most electric shade of pink. The idea that this photograph will infinitely outlive its subject is a microcosm of the nature of photographic evidence. Almost all photographic images can outlive their live subjects. Not only will this moment pass, and this flower pass, but ultimately this photographer will pass too. So this record of what I saw is also a record of me.

Documentary Online Response #4 - The Observational Mode

I found it very interesting to ponder Italian Neorealism as an informing influence for Cinéma vérité. I had not noticed the correlation before, largely because of the intense pessimism that is often inherent in Italian Neorealism, and not as often or as severely so in vérité.

Interestingly, despite an emphatic shift away from the authorly, poetic, movements that predated them, both neorealism and vérité tend to find their strength in striking, bold imagery, with images that would be impossible to achieve in a more tightly controlled environment or with more cumbersome equipment. The sense of kismet that tends to accompany these images and sequences in vérité renders them all the more memorable.

I am coming to terms with thinking of the observational mode of Cinéma vérité as more of a style of storytelling than as an actual reality in filmmaking. That it is more that the filmmaker wants to create the impression of having been an invisible, detached observer, than that they actually managed to be one. In this context, the stylistic choices like a lack of voiceover narration, the use of handheld equipment, and longer takes allowing for more spontaneous dialogue by and between social actors contribute to a distinct type of storytelling that strives to create an effect of fidelity to lived events and historicity. I really want to know what happens when Observational/Cinéma vérité filmmakers have long conversations with cultural studies scholars (like Raymond Williams, discussing the elusiveness of capturing the "structure of feeling" of anyone's lived reality and the repercussions of the selective traditions that form, determining which elements of any lived realities will be remembered and ultimately become historically representative of that cultural moment in history.)

Nichol's extensive collection of ethical questions for documentary filmmakers seems especially relevant for Cinéma vérité practitioners, who usually strive to make their voice in a film invisible, as though the story was telling itself, and as though the viewer's experience with the film were somehow an abbreviated, but comprehensive substitute for having actually been present for the events portrayed. If it's not going to be obvious to viewers that a film represents one person's perspective on what happened, then the one person who's unique experience is shaping the film has an added measure of culpability if the ethics of their filmmaking come into question.

The films we watched in class for Observational Mode (Lonely Boy (1962), Primary (1960), and The War Room (1993) were all interesting for pondering the ethics discussed by Nichols. The not-entirely flattering depiction of Paul Anka's agent in Lonely Boy, for example, provides a distinct example of choices made by the filmmaker (in editing, largely) that dramatically affect the way one person is portrayed.

Interestingly, the same is true about the rather sympathetic portrayals of James Carville and George Stephanopoulos in The War Room. Certainly the footage was compiled and juxtaposed in a way that rendered those two persons more interesting and relatable than they could have otherwise come off, while other individuals, who were largely occupying the same space at the same time, become almost invisible in the film; proof of the subjectivity of the camera.

Il Posto - 1961 - Dir. Ermanno Olmi

Interestingly, despite an emphatic shift away from the authorly, poetic, movements that predated them, both neorealism and vérité tend to find their strength in striking, bold imagery, with images that would be impossible to achieve in a more tightly controlled environment or with more cumbersome equipment. The sense of kismet that tends to accompany these images and sequences in vérité renders them all the more memorable.

I am coming to terms with thinking of the observational mode of Cinéma vérité as more of a style of storytelling than as an actual reality in filmmaking. That it is more that the filmmaker wants to create the impression of having been an invisible, detached observer, than that they actually managed to be one. In this context, the stylistic choices like a lack of voiceover narration, the use of handheld equipment, and longer takes allowing for more spontaneous dialogue by and between social actors contribute to a distinct type of storytelling that strives to create an effect of fidelity to lived events and historicity. I really want to know what happens when Observational/Cinéma vérité filmmakers have long conversations with cultural studies scholars (like Raymond Williams, discussing the elusiveness of capturing the "structure of feeling" of anyone's lived reality and the repercussions of the selective traditions that form, determining which elements of any lived realities will be remembered and ultimately become historically representative of that cultural moment in history.)

Nichol's extensive collection of ethical questions for documentary filmmakers seems especially relevant for Cinéma vérité practitioners, who usually strive to make their voice in a film invisible, as though the story was telling itself, and as though the viewer's experience with the film were somehow an abbreviated, but comprehensive substitute for having actually been present for the events portrayed. If it's not going to be obvious to viewers that a film represents one person's perspective on what happened, then the one person who's unique experience is shaping the film has an added measure of culpability if the ethics of their filmmaking come into question.

The films we watched in class for Observational Mode (Lonely Boy (1962), Primary (1960), and The War Room (1993) were all interesting for pondering the ethics discussed by Nichols. The not-entirely flattering depiction of Paul Anka's agent in Lonely Boy, for example, provides a distinct example of choices made by the filmmaker (in editing, largely) that dramatically affect the way one person is portrayed.

Interestingly, the same is true about the rather sympathetic portrayals of James Carville and George Stephanopoulos in The War Room. Certainly the footage was compiled and juxtaposed in a way that rendered those two persons more interesting and relatable than they could have otherwise come off, while other individuals, who were largely occupying the same space at the same time, become almost invisible in the film; proof of the subjectivity of the camera.

Tuesday, May 13, 2014

Documentary: The War Room (1993)

Ah, politics.

Monday, May 12, 2014

Documentary: Primary (1960)

Another example for Observational Mode.

Documentary: Lonely Boy (1962)

For Observational Mode.

Saturday, May 10, 2014

Documentary Online Response #3 - The Expository Mode

According to Bill Nichols, "The idea of voice is... tied to the idea of an informing logic overseeing the organization of a documentary." As we discussed in class, if Zana were only a subject and not also a director of this piece, the voice would be weighted differently. But because she comes across as our storyteller and our lens, it has both an autobiographical and a participatory bent to it. She certainly appeals to a certain Western morality and standard of living for the film's perspective on the squalor of the children it featured. Their situation certainly seems more dire in contrast to the esteemed gallery events that featured their photographs within the film than it might have in comparison with other poverty-stricken cultures or societies. The starkness of the contrast that was included in the film, along with the effect it seems designed to provoke, are evidence of the construction, voice, and desired effect of the filmmaker(s).

Nichols also said that "the voice of the film betrays its maker’s form of engagement

with the world in a way that even he or she might not have fully

recognized. It speaks from and reveals a

distinct perspective on the world." Zana's outsider-ness in this culture she's determined to make a study of and participate in is ever-present. She never manages to assimilate into this culture - she has no desire to. And so while she verbally proposes her intent to "let the children tell their own story... through their photographs," the film never becomes about their stories, but rather about how their stories fit into, inform, and catalyze Zana's story.

The rhetoric of this film, and the assumption underlying Zana's quest to secure boarding school admittance for these children, rely on the type of "common sense" rhetoric that Nichols found common in documentary. "Common sense makes a perfect basis for this type of

representation about the world because common sense, like rhetoric, is less

subject to logic than to belief." Certainly the film is sympathetic toward Zana's zeal for education as the only constructive option for these kids, and unsympathetic toward all those institutions and individuals who did not share her passion (extending even to the kids themselves.) This belief in education functions within the film as an assumed shared belief with the audience. (It is likely a nearly universally held value among English speakers likely to be choosing to watch a documentary about a social issue - so it's a pretty safe belief to build a rhetorical argument upon.)

_________________________________

Born Into Brothels: Calcutta's Red Light Kids. Dir. Zana Briski and Ross Kauffman. Perf. Zana Briski. Red Light Films/HBO/Cinemax, 2004. Film.

Nichols, Bill. "What Gives Documentary Films a Voice of Their Own?" Introduction to Documentary. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2010. 67-93 and 167-171. Print.

≈

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)